How Outlaw Country Changed Country Music

Outlaw Country

Written by Brent Borman, Mark Anderson & Will Glass. 3 September 2014.

Reprinted by Permission from https://sites.utexas.edu/countrymusic/the-history/outlaw-country/

During the 1950’s and 1960’s, country music experienced the commercial and artistic success known as the Nashville Sound. By the 1970’s, however, it was clear that the Nashville Sound was simply not working for many country artists. It was nearly impossible for new or unfamiliar artists to get any attention, and the artists that did get the producers’ attention were not allowed to write their own songs or hire their own band members. A group of disgruntled Nashville musicians, later known as Outlaws, felt the immediate need to change the system. These musicians began a tradition of creative control and musical experimentation that remain the “bedrock musical values” of country music (Flippo 289).

One of the first musicians to demand creative control over his music is Outlaw country artist Waylon Jennings. Jennings had grown weary of the limitations imposed on him by the record labels, especially as he saw rock bands exercising creative control while operating on a large budget. When it came time for him to re-sign with his record label RCA, Jennings demanded the freedom to record whatever songs he wanted, wherever he wanted, and with whomever he wanted. After tense negotiations, Jennings was granted complete creative control over his music in a contract that Chet Flippo deems “precedent-setting” (277). Waylon’s subsequent albums expressed the independent, anti-authoritarian sentiments of the time and portrayed him as a dangerous, masculine figure.

In 1975, up-and-comer Willie Nelson became the subject of a bidding war between Columbia Records and Warner Bros. Records. He ended up signing a contract with Columbia that granted him complete artistic control over his next album, the same freedom that Waylon Jennings had been given by RCA. After three days and $20,000 in studio costs he presented the Red Headed Stranger, an album that the Columbia Records producers thought sounded sparse and unfinished. While they thought it sounded more like a demo than an album, the contract required them to release and promote the album as Nelson wanted it. Despite Columbia Record’s doubts, Red Headed Stranger was an album that Flippo says “legitimized and intellectualized country, and immediately made country a mainstream popular phenomenon” (281). Both country fans and the mainstream praised Nelson’s willingness to incorporate blues and folk elements into his music.

Outlaw country music reached its climax with the release ofWanted! The Outlaws (1976), a compilation of songs from none other than Waylon Jennings, his wife Jessi Colter, Willie Nelson, and Outlaw musician Tompall Glaser. In a music industry where sales of 300,000 were considered exceptional, Wanted! The Outlaws sold more than one million copies and became the first country music album to be certified platinum. The Outlaw movement was changing as “their creative period ended, and the commercial period began” (Flippo, 288). Waylon Jennings won CMA’s Male Vocalist of the Year Award in 1975 and Willie Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger became country music’s first triple-platinum record. By the end of the 1970’s, it was nearly impossible to miss one of Willie or Waylon’s singles on the radio at any given moment.

Despite becoming commercialized, Outlaw country undoubtedly imparted core values to the country music community. Waylon Jennings inspired country musicians to stand up for their rights and their own way of doing things, and Willie Nelson’s musical experimentation continues to develop and influence the music community. As a result of the Outlaw movement of the 1970’s, country music artists were able to begin exercising independence and freedom over their music.

Key Figures:

Waylon Jennings (1937-2002) is one of the most important figures in the Outlaw Country movement. A musician since his early years, Waylon began performing on KVOW radio at age 12 and had a band called The Texas Longhorns. When he was 21, Buddy Holly became his mentor and helped arrange his first recording session. This was a huge breakthrough for Jennings, as Holly then hired Jennings to play bass in his band. Tired of the producer-run music industry in Nashville, Jennings insisted for creative control over his music and was reluctantly granted his wish after considerable fighting with his record label. Jennings released his album Ladies Love Outlaws in 1972, which was one of the first real approaches to Outlaw Country and became a massive hit. Jennings was able to fully embrace the Outlaw movement after being given creative control, and made his contribution with his subsequent albums Lonesome, On’ry and Mean and Honky Tonk Heroes. He also collaborated with other artists such as Willie Nelson, Tomball Glaser, and his wife Jessi Colter on the album Wanted! The Outlaws, which became one of the main albums known to the Outlaw movement. In addition to being a key player in the movement, Jennings conveyed an overall sense of recklessness and freedom, making him a true Outlaw at heart.

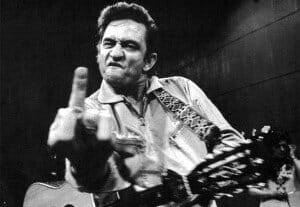

While dominating the Nashville side of the “Outlaw” movement, Johnny Cash (1932-2003)‘s use of drugs and drinking during the 1960’s and 1970’s developed him into a true Outlaw. According to David Allan Coe, there was a difference between being an “Outlaw”, and simply making Outlaw music. Cash definitely proved to his audiences that he qualified in both of these aspects. These problems lead to a fall in the 1970s, but later Cash regained his stability and his music helped change country music for the better. Cash is a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame and won several Grammy Awards.

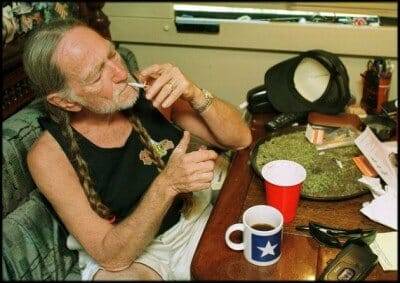

In the early 1970’s, Texas native Willie Nelson (b. 1933) was just another struggling Nashville musician whose records weren’t selling. When a fire burned down his Nashville home, Nelson uprooted himself from the conservative music scene and moved to Austin, Texas. Nelson quickly found himself at the center of Austin’s countercultural activity by playing at venues such as the Armadillo World Headquarters, a club where Nelson was able to play a plethora of unique music ranging from hillbilly to blues to rock to soul. Austin’s sound was much more free-spirited and experimental than Nashville’s, and the city began to inspire and shape Nelson’s identity as an artist. His albums Shotgun Willie (1973) and Phases and Stages (1974) helped resurrect his music career and establish an identity for himself as an artist. His next album the Red Headed Stranger (1975) was certified multiplatinum and is one of the most essential albums for Outlaw country music. Red Headed Stranger is a concept album that tells the story of a man who kills his cheating wife and mournfully roams the countryside in search of redemption. By insisting on doing things his own way, Willie Nelson brought Outlaw music and his career to the national spotlight.

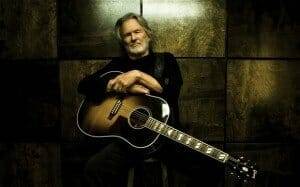

In 1965 Kris Kristofferson (b. 1936) moved to Nashville, the origin of the Outlaw country movement and the place where he would eventually find his success. Kristofferson was a gifted vocalist who knew how to play the guitar very well, but struggled to find success in his music and ended up taking a job at Columbia Studios in Nashville sweeping floors. After meeting famous artists such as Johnny Cash, he was given his chance and began collaborating with other famous figures in the Nashville Outlaw scene. In 1985 he joined the country music “supergroup” called The Highwaymen, which included Outlaw superstars Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and Johnny Cash. He was a significant contributor to the Outlaw movement due to his reckless, unmistakable attitude. In 2004 Kristofferson would go down in history yet again, as he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame with the other legends of the Outlaw genre.

Recommended Listening:

- “Cocaine Blues” (Johnny Cash, At Folsom Prison, 1968): The story of a vengeful and redemptive husband is a recurring theme in Outlaw country music. “Cocaine Blues” is the tale of a man who kills his adulterous wife and flees to Mexico, only to be captured and sentenced to 99 years in Folsom Prison. This track is significant not only for telling an archetypal tale of the Outlaw figure, but also because it marks a shift away from the tradition of recording in the studio for producers. “Cocaine Blues” was recorded live at Folsom State Prison for an audience of real-life Outlaws.

- “Whiskey River” (Willie Nelson, Shotgun Willie, 1973): From Willie Nelson’s defining album Shotgun Willie, “Whiskey River” is a song about a man in the midst of his sorrows due to his lover having left him. The chorus, which repeats “Whiskey river take my mind / don’t let her memory torture me / Whiskey river don’t run dry / you’re all I’ve got take care of me”, shows the genuine turmoil undergone by this man and his inability to cope with it. Heartbreak and loss are common themes in Outlaw country music, and the bluesy sound and guitar solos make this track an example of the new country sound that many Outlaw country artists were experimenting with.

- “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean” (Waylon Jennings, Lonesome, On’ry and Mean, 1973): The title track from Waylon Jennings’ album Lonesome, On’ry and Meantells the story of a rambling man who travels to New Orleans for gambling and sex. There he meets a prostitute named Codene who he believes will help him stop being lonesome, on’ry and mean. After an evening of debauchery, at dawn he finds himself praying for God’s intervention. The Outlaw’s vulnerability and longing for companionship is shown briefly as he prays for the Lord to help him change his ways and find what he desires so badly.

- “Bob Wills Is Still the King” (Waylon Jennings, Dreaming My Dreams, 1975): This song from Waylon Jennings was written in 1975, the year Bob Wills passed away. The track is letting the listeners know that Bob Wills had an impact on the Western Swing genre in Jenning’s music. He mentions Austin, Texas thoroughly throughout the song, which was one of the main homes for the Outlaw movement. Jennings talks about how the “Honky Tonks in Texas were my natural second home”. He mentions the hard times in he went through the Outlaw movement, and that he is still proud to be from Texas.

- “I Couldn’t Believe It Was True” (Willie Nelson, Red Headed Stranger, 1975): This short track from Willie Nelson’s landmark concept album describes the beginnings of an infamous Outlaw, the Red Headed Stranger. The Stranger is a man who descends into sorrow and madness after he catches his wife in bed with another man. The Outlaw’s sorrow and turmoil (“And my eyes filled with tears and I must have aged ten years”) along with his anger (“And I’ll try to forgive but I cannot forget, my heart break and loss is another man’s gain”) are the catalysts for his dangerous behavior and the violent events that unfold.

- “Red Headed Stranger” (Willie Nelson, Red Headed Stranger, 1975): The title track from Willie’s multi-platinum album Red Headed Stranger continues the tale of the Stranger, as well as providing a warning to anybody who might encounter this Outlaw figure. The Stranger, who is described as “wild in his sorrow” and with a “heart heavy as night”, becomes a dangerous and violent figure after discovering his wife’s treachery. Without spoiling too much of the narrative, the Red Headed Stranger is an incredible album that sets the foundation of the archetypal Outlaw journey from sorrow, violence, and loss to redemption and newfound love. The Red Headed Stranger as an album is essential to Outlaw country music’s history.

- “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” (Waylon Jennings, Dreaming My Dreams, 1975): “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” serves as an open critique of Nashville’s country music industry condition at the time. The title is a reference to Hank Williams, one of the most influential singers and songwriters of the 20th century who laid much of the foundation for country music. Waylon Jennings directly questions Nashville’s repetitive tunes and flashy lifestyle, revealing that he doesn’t think Hank made music this way and that “we need to change”. The track was released in the year that Waylon Jennings won CMT’s Male Vocalist of the Year award, only emphasizes the success that the Outlaws found by deviating from the tired Nashville formula.

- “Willie, Waylon and Me” (David Allan Coe, Rides Again, 1977): This track from David Allan Coe places Outlaw music in the context of other significant music movements of the time. Coe recalls that in the midst of other music crazes, such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, the talk turned to Outlaws who were playing free-spirited music with their bands in Texas. This song emphasizes the importance that Willie, Waylon, Coe, and the other Outlaws had in the music movement.

Annotated Bibliography:

1. Bane, Michael. “Outlaw Fever.” The Outlaws, Revolution in Country Music. New York: Doubleday, 1978. 112-119. Print.

As a result of the very well known Outlaw music that was constantly being made, society, as they knew it in Nashville was going to change. As Bane (the author) describes it, all hell broke loose in Nashville right after the Wanted! The Outlaws album was released to the public. “It sold like crazy, easily outstripping all the country records that had gone before it” (114). To most fans, Outlaw music was a lifestyle and it came with a certain feeling of freedom and recklessness. It was the first country album in history to sell over 1 million copies and become certified platinum. There became a big popularity involving drinking Jack Daniels whiskey and doing cocaine around this time, as well. “Jack Daniels Black Label whiskey became the common denominator of everyone aspiring to Outlawism” (116). According to Bane, “you couldn’t be an Outlaw without a coke (cocaine) stash” (116). This shows how much of a societal change Nashville went through almost overnight. Bane noted “everyone in town started looking like bit-players from The Wild Bunch,” (116) so it was becoming quite obvious how far the Outlaw influence was spreading, in Nashville especially. “Executives grew beards and receptionists shucked most of their clothes, and each day it got a little worst” (116). According to Bane, Outlaw country artists broke “through the excesses of the mainstream Nashville music business” (119), along with the changes to everyday life it entailed. In the end, the Outlaws and their music helped to shape the city of Nashville and the way people listened to music in general.

2. Jennings, Waylon. This Time. Buddha Records. 1974. CD.

In 1972, Waylon Jennings was finally given a place in Nashville’s 1970 Outlaw movement; with his never give up attitude and the help of his longtime friend Buddy Holly. To get to this point he fought tough negotiations with RCA Victor Records, which were unheard of for any country artist, but eventually he was granted the creative freedom reserved for only the big name rock stars. According to the author of the booklet that comes with the CD (Rich Kienzle), This Time was one of the main “commercial and artistic triumphs that would define Waylon Jennings for all time.” In October of 1973, Jennings and co-producer/musical alter ego Willie Nelson started recording this CD. “The title song was a vindication: a Waylon original from the late sixties that RCA initially rejected. Now, in 1974, it became his first #1 single.” It was Jennings’s best-selling LP ever, and remained on the charts for over six months following its initial release. In 1973, Jennings’s became the famous Buddy Holly’s protégé. “Holly produced Waylon’s first single in 1958 and, in January 1959, touring without The Crickets, hired Waylon to play bass.” Holly had a very strong faith in Jennings and his potential, and influenced him to who he became as an artist. Ultimately, This Time was an incredible example of Jennings fulfilling his mentor’s (Holly) faith in him and taking that next step in his genre of music.

3. King, Stephen A. “‘Between Jennings and Jones’: Jamey Johnson, Hard-Core Country Music, and Outlaw as Authenticating Strategy.” Popular Music and Society 31.1 (2014): 1-21.Taylor and Francis Online. Web. 3 Sept. 2014.

In this article, Jamey Johnson’s story is told from his humble beginning as a Nashville hopeful to full on country Outlaw. Johnson associated “himself with the original 1970s Outlaw movement and including folklore elements of the American Outlaw-hero in his songs.” Johnson wasn’t actually even labeled as an Outlaw (but was born during the Outlaw movement in the 1970s), until the release of That Lonesome Song in 2008. He was an authentic successor of the Outlaw movement of the 1970s, and King noted, “The country Outlaw movement was largely a response to the country music sound emanating from Nashville, a city which has long promoted itself as “Music City U.S.A.” or, alternatively, “The Country Music Capital.” In his music, he conveys experiences shared very similarly to those of Jennings, Nelson, and other big hits. Johnson’s significant debut album, The Dollar, was released in 2006 and according to King, “he was not marketed as a rebel or an Outlaw or even characterized by journalists and observers as such.” According to King, “the concept of the Outlaw was one who works outside the confines of the law to uphold universal justice for all.” All in all, Johnson came from the Outlaw era and eventually became the full-fledged one that we know today. He tied in memories from the 1970s with more of a current sound, making him unique and very much still in the country music game.

4. Flippo, Chet. “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” Will the Circle Be Unbroken: Country Music in America. By Paul Kingsbury and Alanna Nash. London: DK, 2006. 271-95. Print.

Outlaw country music had a significant impact on mainstream culture as well as the country music community. While Jennings and Nelson had singles all over the radio and were the recipients of several Country Music Awards, they also set the standard of complete artistic control over their own music. Outlaw artists irrevocably changed the artist-producer relationship by demanding creative freedom from their record labels. Waylon Jennings set a precedent for the rights of country musicians by demanding control over his own music. Willie Nelson made country music popular even among mainstream audiences. Following their success, the creative period of the Outlaw movement had ended and the commercial period had begun.

5. Stimeling, Travis D. “Narrative, Vocal Staging and Masculinity in the ‘Outlaw’ Country Music of Waylon Jennings.” Popular Music 32.03 (2013): 343-58. Academic Search Complete. Web. 3 Sept. 2014.

In the early 1970’s, a group of country artists challenged the standard business practices of Nashville’s recording studios. These musicians, later named ‘Outlaws’ by the press, challenged the producer-run industry and took control over their artistic property. One of these emerging Outlaws was Waylon Jennings, who provided a public critique of the Nashville system as well as the authenticity of white working-class masculinity. Jennings’ 1972 album Ladies Love Outlaws characterized the Outlaw as a wild-eyed and dangerous man, propelled out of control by sorrow and loneliness. Lonesome, On’ry and Meanreleased in 1973, and began to show another side to the angry and unpredictable outlaw. In the title track, the speaker retreats to a Greyhound bus to pray for God to save him from his loneliness and rambling ways. Waylon’s vulnerability is realized in his 1975 album Dreaming My Dreams, in which he demonstrates deep feelings for a former lover. The refrain, “Someday I’ll get over you”, offers an explanation for the Outlaw’s sorrow and unpredictable behavior. He resolves to believe in love, and “Give it away, as much as I can”. The Outlaw’s internal conflictions between rambling life and domestic life is resolved as he reconciles with his mistakes. The Outlaw antihero learns to not simply retreat to the bottle or the arms of another woman. Rather, he turns inward, searching for the source of his discontent, openly expressing his fears, and standing alone in an unfriendly world.

6. Stimeling, Travis D. “‘Phases and Stages, Circles and Cycles’: Willie Nelson and the Concept Album.” Popular Music 30.03 (2011): 389-408. Academic Search Complete.Web. 3 Sept. 2014.

Concept albums were a format used by many rock bands in 1960’s and 1970’s. Ripe with compositional possibilities, the concept album was largely ignored by the Nashville country music community. A few artists working on the fringes of the scene, later known as Outlaws, began to experiment with the concept album as they aligned themselves with the countercultural images and attitudes of the time. One result was Red Headed Stranger, the 1975 concept album by WillieNelson. Recorded in a non-label recording studio, the label executives did want to release the album until significantly more work was done on it. Willie Nelson’s contract made him the final arbiter in the decision making process, so the album was released. By firmly rejecting the sounds and practices of Nashville, Nelson solidified himself as a countercultural icon as well as a talented musician. Red Headed Stranger became a staple Outlaw country music album, and the single “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” reached the number one spot on the Billboard “Hot Country Singles” chart. The album tells the story of a preacher who, after murdering his wife and her lover, wanders through the mountains with her horse in search of solace and redemption. After killing another woman for touching the horse, he arrives in Denver where his love with a new woman helps him forget his pain. The archetypal Outlaw journey is set forth for the listener, as the album’s side A tells of the stranger’s pain and quest for redemption and side B depicts him as a protagonist who is able to find love again. Similar to other Outlaw artists, the narrator is presented as a damaged man whose psychological turmoil has made him wild in his sorrow.

7. Streissguth, Michael. Outlaw. New York: HarperCollins, 2013. Print.

In Streissguth’s book Outlaw, he goes deep into the lives of Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson during the 1960’s and 1970’s. This “Outlaw” movement would go on to change country music forever. Streissguth states when talking about these men: “They resisted the music industry’s unwritten rules, which prescribed the length, the meter, and the lyrical content of songs as well as how those songs were recorded in the studio” (Streissguth 2). As we also learned in the book Turkey In The Straw, many record companies of this time told the artists exactly what they could record, and who they recorded it with. Streissguth does a great job explaining how Jennings, Kristofferson, and Nelson changed this scene into what record deals are like today. He gives background information on these artists childhood, and how they became the stars that they are now. Streissguth’s book leads you step-by-step, taking you from Texas to Nashville, in the development of the “Outlaw” movement.

8. Thomson, Graeme. The Resurrection of Johnny Cash: Hurt, Redemption, And American Recordings. London: Jawbone Press, 2011. Print.

In Graeme Thomson’s book, The Resurrection of Johnny Cash: Hurt, Redemption, and American Recordings, he tells us the amazing story of Johnny Cash’s turnaround in the music industry. In Ray Waddell’s article, “Shaver and Coe: Two Outlaws Look At Sixty”, he mentions David Allan Coe saying that an “Outlaw” did something criminally wrong and “Outlaw music” was when you were musically different. In this book we see that Johnny Cash was both of these, from drugs and drinking in the 60’s and 70’s, to revolutionizing music after his post 1970 fall. “Heaven knows Cash’s demons were real enough, and they were very much part of what made him the man he was from cradle to grave” (Thomson 22). There was an “Outlaw movement” in both Nashville and throughout Texas. While Jennings and Nelson seemed to be dominating the Texas side, Cash had his own television show, The Johnny Cash Show, which ended in 1971. Soon after, we learn Cash let drugs and drinking get the best of him while his music career was dying down, but it wouldn’t last forever.

9. Waddell, Ray. “Shaver and Coe: Two Outlaws Look At Sixty.” Billboard 113.42 (2001): 75. Music Index. Web. 15 Sept. 2014.

In Ray Waddell’s article “Shaver And Coe: Two Outlaws Look At Sixty”, he emphasizes the impact David Allan Coe and Billy Joe Shaver had on the “Outlaw movement” in the 1970’s. Waddell states that there was no artist during this time that had more credible “Outlaw” traits than Coe. He also lets us know that Shaver worked with Jennings to kickoff the whole “Outlaw movement”. Waddell tells us that Coe’s appearance of tattoos and “biker looks” made him look like he could create an “Outlaw” type of song. Coe believed “Outlaw” and “Outlaw music” were two separate things. If you were an Outlaw, he states, then you then you did something criminally wrong, but musically you had to be different. After reading this article, one notices Coe’s music was definitely different. According to the author, Billy Joe Shaver helped start the entire Outlaw scene by letting Waylon Jennings record Shaver’s own Honky Tonk Heroes. Shaver states: “after that album hit, which everybody said it wouldn’t, everybody else changed, too” (Waddell 75). Waddell sums up the article by telling us that Shaver wouldn’t have it any other way when thinking of the country Outlaw movement. He says it was a wild time, but he still had fun.

Discover more from Making A Scene!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.