Gain Staging: What to know, & why you shouldn’t stress too much about it!

Gain Staging: What to know, & why you shouldn’t stress too much about it!

(This is a script to a video that will be included in an upcoming series on post production. I decided to make the script its own post because of the amount of confusion there is on the topic, and because of the amount of time it’s taking me to complete the series thanks to other responsibilities. Thanks to Matthew Weiss, Eric Van Wagner, Daniel Robert Ford, and others for answering questions during my research. You know who you are.)

—-

There’s a lot of emphasis placed on gain staging. While it is important to understand, it’s also exaggerated in many blogs and forums as the lynchpin between a good mixer and a bad mixer. We’ll spend a few moments discussing what you should know, and hopefully you’ll see why you shouldn’t stress out about having perfect levels during production & mixing.

Gain staging is nothing more than setting appropriate input & output levels. That’s all. However, what is appropriate will depend on what you’re trying to accomplish and what piece of gear you’re setting levels for. Analog gear is non-linear, and different levels will cause it to react in different ways. DAW mixers are linear, which means the sound will be unchanged by the level. As long as you’ve got a healthy enough level to keep the noise floor at bay while avoiding overloading or clipping at the converter, you’re pretty much set in the digital realm. Let’s dive further, and we’ll start with analog.

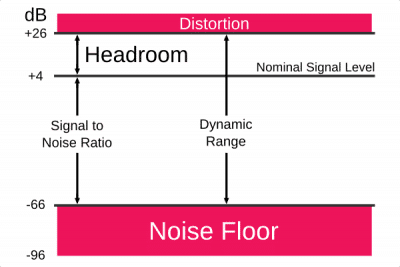

Analog gear is designed to operate at a certain optimized level. This is due to the number of physical hardwired connections inside of the piece of gear in question, and those levels can be measured differently depending on whether the item is consumer grade or professional grade. These connections create a certain amount of low level noise, known as the Noise Floor. This noise floor exists in any physical connection, including the connections we make to our audio interfaces with mics and DI’s. We’re not going to dive too deep into signal-to-noise ratios, but your unit was designed to operate at an optimized level in order to keep the signal-to-noise ratio high enough to avoid a substantial noise buildup during mixing. This optimized level is also low enough to avoid non-linear saturation and clipping. We should aim to hit the input level our gear was designed to handle, while understanding what can happen when we go lower and higher with our analog gear. Going lower can decrease the signal-to-noise ratio, which increases the risk of a noise buildup in your mix. However, because of the non-linear way the circuit reacts to the signal, pushing less signal into the circuit will change the way the analog circuit reacts to the audio. This may be pleasing to your ear, and if it is you should go ahead while being aware of the increased risk of a noise buildup as you add dynamics processing during mixing. On the flip side of this, going for a hotter signal can create pleasing saturation and distortions on our sources. This can be used intentionally as an effect to change the character of the sound, but if you’re not trying to add such an effect you should avoid over-saturating the signal.

It’s important to understand what happens at the input stage as well as at the output stage of your analog gear. Some pieces will have input circuits designed to help add color to your sound, like that of a mic preamp. The same unit may have an output circuit designed to avoid coloring the sound further than you already have, that way you can set the appropriate color at the input and not alter the sound further at the output stage while you’re trying to set the appropriate output level. The input and the output stages can both be pushed into distortion, but each will likely offer a different flavor of distortion when pushed because of the different circuit types involved. Understanding how your unit reaches saturation and distortion is important, as it can help you track down unintentional distortion as well as helping you understand how you can use your unit in creative ways.

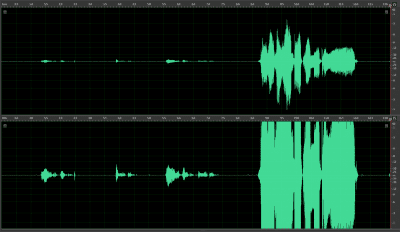

Digital, on the other hand, is less forgiving. A/D converters always have an analog front end, which means they have an inherent noise floor associated with them. We need to push enough signal into the converter to avoid noise floor problems later on. However, with digital we can only push so far before the circuit starts to fail and we get digital distortion and digital clipping. When we clip at the digital converter, the sound above the ceiling is just cut off completely. This adds distortion that isn’t always desirable, but it can be useful in certain situations. While digital clipping can be a desired effect, there are tools designed to give controllable clipping within our DAW’s. If we’re trying to clip digitally, it’s still advisable to record it clean and clip it during post production. That way we don’t risk accidentally going too far, and we can try out different clipping flavors to see what sounds best for our sources.

Since digital is linear, once we’ve passed our converters the sound doesn’t saturate based on level the same way analog gear will. This means instead of pushing a hotter signal to get a particular tone, we’re merely trying to stay high enough to avoid the noise floor while staying low enough to avoid overloading or clipping as we record. There’s no reason to push a hot signal into our converters, unless we’re trying to intentionally clip on the way in, and since that can be handled in a more efficient way in post we should make sure we’re keeping our levels somewhat conservative at our converters. A good target range to shoot for with your average levels is anywhere above -20dbfs with our maximum peaks hotting no hotter than -10dbfs. That will depend on your converters, of course. My own interface begins overloading with visible signs of distortion after -10dbfs, so I try to record with my max peaks hitting no hotter than -10dbfs. I’ll typically shoot for -12dbfs, and if I overshoot by a db I don’t stress out. I’ve still got headroom to avoid overloading, and I’m way above the noise floor.

Here, yet again, we need to understand the capabilities of our gear. Apogee converters have implimented a soft limiting feature that allows you to push more signal into the converter as a way of saturating the signal’s analog front end before it gets converted to digital. The soft limiter prevents clipping from occurring as you push more signal into the converters analog stage for tone. Knowing what your gear is capable of will allow you to know when you can push these boundaries thanks to intentional design elements such as this. With that being said, this soft limiting feature is just another way of getting analog tone in a digital system, and there are plenty of products out there designed to help us get analog saturation within our DAW. I wouldn’t stress out over not having this feature in your converters if I were you.

Once we’re in the digital realm, if we don’t plan to use plugins that emulate the non-linearities of analog gear, we don’t really have much to worry about aside from the gain structure of our plugins and whether our master bus is clipping. Our plugins often have an input and output control, just like our analog gear. If the plugin isn’t modeling analog non-linearities, we don’t have much to worry about in terms of input level. Some of our plugins can still clip internally, but not all, so it’s important to know your gear and how far you can push it.

DAW mixers these days offer a lot of headroom by design. Even though you may see a clip indicator on the channels of your DAW, unless you’re using a 16 bit system you likely aren’t actually clipping. These clipping indicators were more of a necessity in the earliest days of digital recording with lower bit rates. With 32-bit and 64-bit systems, as long as you’re not clipping at the master fader, you’re not clipping.

So if we aren’t clipping at the daw channel, why do we have clipping indicators? Simple. If our channel clipping indicator goes off, and we’re sending that channel’s output to an analog converter so we can use a piece of analog gear that we have, then we are actually clipping. Once the sound leaves the digital world, that clipping indicator becomes important again. But if you’re remaining in the box for everything, you’ve got much less to worry about thanks to nearly infinite headroom.

The bottom line is simple. Gain staging isn’t some mystical formula based on a number that we all must reach for in terms of our gain structure. It’s merely setting the appropriate input & output levels. In order to do that, we have to know what we’re trying to achieve. We have to know the gear we’re using, and what it will do when set to various levels. We have to know what happens at our converters. And we have to understand when we’re clipping and when we’re not clipping within our DAW. Aside from that, don’t stress too much about setting the perfect level. Just set it for what you’re trying to accomplish and move on!

Discover more from Making A Scene!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.