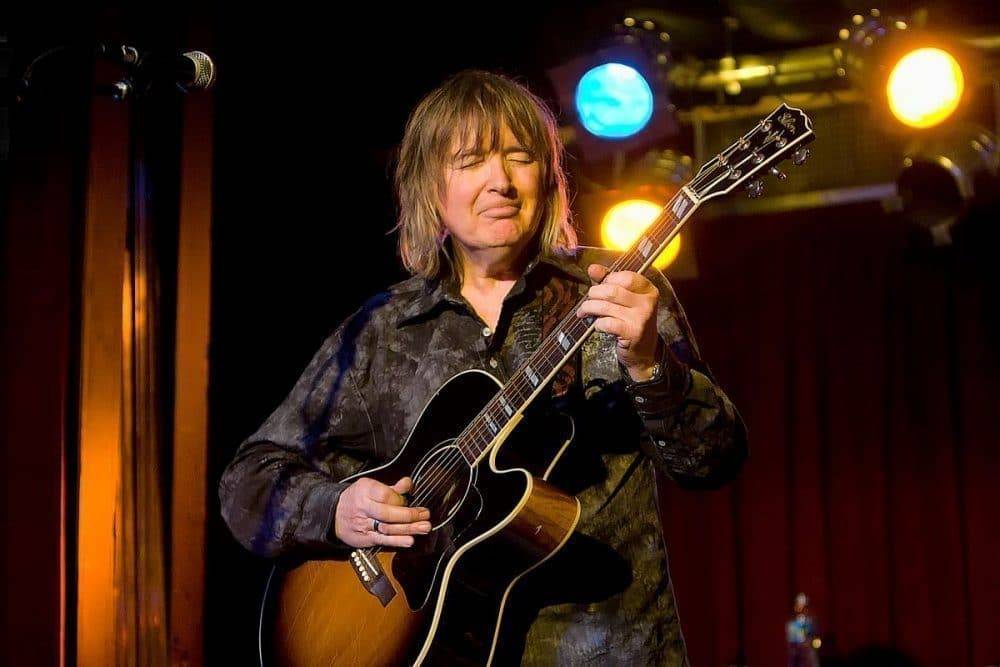

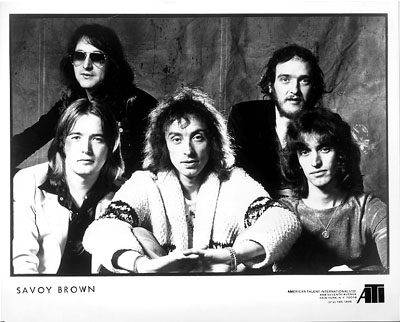

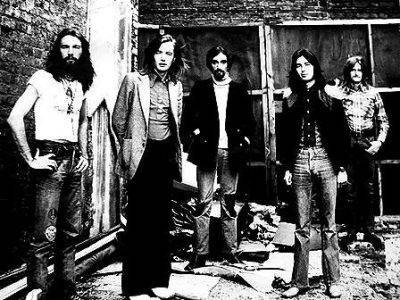

An In Depth Interview with Kim Simmonds of Savoy Brown

Originally called the Savoy Brown Blues Band, this group can rightly take credit for cutting the farewell anthem of the 1960s British blues boom, in the form of a modern blues aptly titled “Train to Nowhere.” Historically as well as musically, this song remains a sad reminder that by the time of its 1969 release as a single, most original blues were no longer commercially viable in Britain, as more and more blues clubs closed their doors for good.

Within four years of the bands formation, however, they had become a major league live act in America. At home in Britain, they weren’t so lucky, and never really broke out of the club scene despite founder/guitarist Kim Simmonds’s (b. December 5, 1947; Newbridge, South Wales) persistence as the band’s only continuous member.

Today, critics believe that one reason for Savoy Brown’s inability to gain a foothold in Britain was its high personnel turnover, but these frequent lineup changes also led to some noteworthy ensembles. Many consider that the recordings featuring Chris Youlden’s rich vocals and songwriting augmented by Kim Simmonds’s jazz-tinged, fluent blues guitar, were Savoy Brown’s finest work; this being especially so on such late-1960s cuts as “She’s Got a Ring in His Nose and a Ring on Her Hand” (a classy swing-blues) and the completely different and desolate groove of “Mr. Downchild.” The early-1970s also saw some interesting personnel changes including a collaboration with Chicken Shack’s Stan Webb (when the band also was known as the Boogie Brothers).

Early in his life, Savoy Brown guitarist Kim Simmonds was heavily influenced by his older brother Harry (christened Henry). Harry Simmonds had started listening to music when he was about thirteen, especially to Bill Haley. He later became interested in R&B and blues, particularly the music of James Brown, Ike and Tina Turner, Jimmy Reed, Otis Rush and Muddy Waters. He often purchased American imports from The Swing Shop, a small record store located in Streatham, Southwest London, which was also a hangout for Jo Ann Kelly.

Kim became absorbed in the records in his older brother’s collection. “My brother, Harry, used to come home with all these records and I used to hear nothing but blues,” he told Beat Instrumental. “I was hooked straight away.” Among Kim’s influences were Howlin’ Wolf (and his guitarist Hubert Sumlin), Earl Hooker, Freddy King, Matt Murphy, Otis Rush and Muddy Waters. At age 13, Kim purchased his first guitar and taught himself to play Chuck Berry riffs. By age 15 he was still playing the guitar, though by then he had dropped out of school and taken a clerical job at the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall.

While waiting outside Transat Imports, a record store located in London’s Chinatown district, Kim met another blues enthusiast, harmonica player and neighbour John O’Leary. O’Leary was working for an American chemical company and had picked up the harmonica after seeing Cyril Davies perform with Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated. O’Leary and Kim became friends and O’Leary invited Kim and his brother Harry to a jam session. “I went along not expecting very much, but Kim had got a really good thing going,” Harry later observed.

He encouraged his brother to form a band and they all agreed that Harry would manage them. The initial lineup consisted of Kim Simmonds on guitar, O’Leary on harmonica, Leo Manning on drums, vocalist Brice Portius, and bassist Ray Chappell. Both Manning and Portius were black, while the other members were white, thus making Savoy Brown one of the first racially integrated groups to play in British clubs.

Their first pianist, Trevor Jeavons, was soon replaced by Bob Hall (who became one of Savoy Brown’s longest-serving, albeit part-time, members). Previously, Hall had been a member of John Lee’s Groundhogs (later the Groundhogs), which had backed John Lee Hooker on his 1964 British tour. He had also played backup to Jimmy Reed and Little Walter. By the time of the Groundhogs’ first recordings, however, Hall had departed because of time conflicts with his day job.

The new group decided to call themselves the Savoy Brown Blues Band to emphasize their Chicago Blues-style repertoire. They took Savoy from the US blues label, Savoy Records, which they thought sounded elegant and “Brown” because they perceived it as being about as plain as you can get. Strung together, the words created a balance of opposites.

Like many bands, they found it tough to get bookings at first, but unlike other bands, the Simmonds brothers simply decided to open their own blues club, Kilroy’s, in May 1966. Kilroy’s was located in an upstairs room of Nag’s Head Tavern on York Road in Battersea. Kim recalled the club to Relix: “They used to have a folk club one night a week and as folk was dying out by then we approached them about having a blues room on Monday nights. We’d take our gear down in a taxi or something like that. We used to rehearse there anyway. From what I can recall, we distributed flyers around London and the club came into being. At first only a few people came and then we played there every week and it built up, and eventually it became a bona-fide blues club. Fleetwood Mac played there, and Freddie King and all sorts of artists.” The Nag’s Head eventually became home to the Blue Horizon club-a place where future British blues talents such as Fleetwood Mac’s Danny Kirwan (then with his first band, Boilerhouse) were discovered.

As the Savoy Brown Blues Band ‘s manager, Harry landed a story about the group and their blues club in the pages of the local Wandsworth Borough News. At the time, Harry (who also worked as a London postman) would enterprisingly take the band to gigs in his Post Office van. Kilroy’s became a local success and soon attracted the notice of Mike Vernon. Along with childhood friend Neil Slaven, Vernon published the blues and soul music magazine R&B Monthly, and was at the time a producer at Decca. Vernon had also established the Blue Horizon label along with his brother, Richard, which included two subsidiary labels, Purdah and Outa-Site.

As Vernon explained in the liner notes of History of British Blues, “I talked Harry Simmonds, their manager, into letting me record the band for a single to be released on my own Purdah label-that was the precedent to Blue Horizon.” They recorded four tracks in August 1966 at London’s Wessex Studios, with Vernon producing. Vernon issued two of the tracks, the Willie Dixon-penned “I Can’t Quit You Baby” and “I Tried,” as a single on Purdah to be distributed by mail order. The other two, “True Blue” (a.k.a. “True Story”) and “Cold Blooded Woman” were assigned Purdah catalog numbers but not released. They eventually came out as part of the Immediate label’s Blues Anytime series.

The band received a big break when Brian Wilcock, a DJ at Klook’s Kleek R&B Club, Railway Hotel located in the West Hampstead area of London and a friend of Harry Simmonds arranged for the band to play the interval for Creams appearance there on August 2, 1966. Since Cream made their official debut at the 6th National Jazz and Blues Festival on July 31, this would be their first club engagement outside of a warmup gig held on July 29 at the Twisted Wheel in Manchester. Expectations were high for the Cream which played two sets but Savoy Brown went down such a storm during their slot that they racked up enough gig offers to enable them to go full time-and Wilcock eventually became their tour manager in September 1967.

The band started to expand their gig list to include engagements at the Tiles Club, Flamingo and the Marquee in central London and the Metro in Birmingham. Kim once said about those early shows, “We started playing places like the Metro in Birmingham, which is like a big soul club, but we managed to please the people because we had Brice Portius, a black singer, and they would relate to him in the sense that they might relate to Geno Washington, even though we were playing blues. I mean we would play up-tempo stuff and bounce around a little.” Several shows even found them backing Champion Jack Dupree. Altogether, their lineup remained stable except for pianist Hall, who once again had conflicts with his daytime job that caused him to drop out for awhile but return on a part-time basis when his replacement didn’t work out. Demos and acetates were recorded with this lineup prior to the sessions for their first album. Ex-Stone’s Masonry guitarist Martin Stone was added while O’Leary departed to become a member of John Dummer’s Blues Band [see John Dummer’s Blues Band]. Both Graham “Shakey Vick” Vickery and Steve Hackett auditioned to play harp during this period, but O’Leary was not replaced.

Decca signed the band on the recommendation of Slaven and Vernon, and by mid-1967 the group was at West Hampstead Studios, London, recording their first album with Mike Vernon again producing. In the excellent Blue Horizon CD set, Vernon discussed his rationale for signing the band to Decca rather than to one of his own labels: “Firstly, Blue Horizon was still, at the time, little more than a fanzine label and secondly, I must herein admit that I didn’t care too much for Brice as a vocalist.”

The Savoy Brown Blues Band’s first Decca long player was recorded in just thirty hours spanning three consecutive days. Shake Down was a gritty collection of blues standards with just one original, Stone’s “Doormouse Rides the Rails.” Among the tracks were B.B. King’s “Rock Me Baby,” John Lee Hooker’s “It’s All My Fault,” three Willie Dixon songs and “Black Night” by Fenton Robinson. The standout track was the group-arranged “Shake ‘Em on Down,” a raucous workout extending to just over six minutes. Shake Down was released in the U.K. in September 1967, but for reasons unknown, the LP didn’t appear at all in the U.S.

The Savoy Brown Blues Band continued to gig extensively while Shake Down was in production, doing a punishing 24 gigs in just 21 days as backing band for John Lee Hooker. They also got a summer-long residency in Charlottenlund, north of Copenhagen, Denmark. At around the time of Shake Down’s release, in an odd coincidence the band experienced a true drug-related “shake down” in Barnstaple, a town in Devon, England, during a short tour of the West Country. This incident led Harry to actually fire his brother Kim from the band after the dates in Denmark. Other changes ensued as Chappell and Portius left and were replaced by Bob Brunning on bass and Chris Youlden on vocals. Brunning had previously been Fleetwood Mac’s bassist for a few weeks in August 1967.

Youlden had been in various outfits, including a band that had alternately called itself the Down Home Blues Band and Shakey Vick’s Big City Blues Band, and another called the Cross Ties Blues Band.

Next, Manning quit and was replaced on drums by Hughie Flint, formerly of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Alexis Korner’s band, Free at Last band. Finally, Stone departed and Kim asked O’Leary to rejoin the band. O’Leary agreed at first, then changed his mind due to “unreasonable conditions.” Stone was instead replaced by “Lonesome” Dave Peverett.

Dave Peverett (b. April 16, 1943; d. February 7, 2000) was born in Dulwich but grew up in Brixton, southwest London. He first got into music after hearing “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley and the Comets. He then listened to Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley before turning on to blues musicians like Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins and John Lee Hooker. At age 16, he bought his first guitar and, with his brother on drums, gathered other musicians and formed a band that played its first party in 1963. After undergoing a series of name changes, the group (whose membership included Chris Youlden) eventually settled on the name the Cross Ties Blues Band. By 1966, they had become the Lonesome Jax Blues Band, named after Dave Peverett’s first stage name. The band played the London club circuit and colleges.

Later, Peverett joined the Swiss blues group Les Questions, with which he played until October 1967, at which point he returned to the U.K. brimming with plans to start a band along with Youlden. Instead, he joined Savoy Brown.

With only Kim (who had since made amends with Harry) and Hall from the prior lineup, the group entered the studio to record their next single. Youlden emerged as a major creative force within the band, contributing the frantic “Taste and Try Before You Buy,” which became the A-side of their next release. Kim had written the flipside, “Someday People.”

Record Mirror praised the band as playing “a style of Chicago blues which is both commercial and authentic” and observed that Youlden was “often rated in the same breath as Long John Baldry and Rod Stewart.”

Shortly after the single was cut the band underwent more member changes. Both Brunning and Flint left; Brunning has since cited the “creative accountancy” of the band’s management as the main reason for walking. (Manager Harry used to pay band members a fixed weekly wage regardless of how many gigs they played and the money made from each gig. From a musician’s point of view, this was a good incentive for not getting too successful). By 1968, Brunning formed the Brunning Sunflower Band with Bob Hall, and Flint went on to early-1970s pop-chart success in McGuinness-Flint, later settling with the Blues Band.

After the Savoy Brown Blues Band had tried out several replacements for drums (including drummer Bill Bruford) and bass, the band decided on Rivers Jobe and Roger Earle, respectively. Jobe had previously been a member of the Anon (from May 1965 to July 1966) with Anthony Phillips and future Genesis founding member Mike Rutherford.

Producer Mike Vernon arranged for sessions for the group’s next album, Getting to the Point, which took place in March 1968. Alongside Kim, Youlden emerged as co-leader of the group, and jointly or separately the pair composed most of the material. While the U.K. version of the album had cover-art depicting Kim wearing round glasses with the image of a black man in each lens, the U.S. cover art depicted more innocuous and politically correct images of a maze breaking up a collage of artwork. Kim explained what the original cover design was trying to depict to Melody Maker: “Our cover tried to show that although we are white we see things the same ways as a Negro but for some reasons it was changed.”

With just two cover songs and seven originals, the album was to have been the Savoy Brown Blue’s Band’s transition from being a blues covers outfit to a band that had asserted its own identity. Unfortunately, the songs were not as strong as the pieces on the previous album, with the exception of the moody “Mr. Downchild” and the Willie Dixon-penned “You Need Love.”

Getting to the Point was released in both the U.S. and the U.K. in July 1968 to positive reviews. Disc Weekly wrote approvingly that the album “showcases their fine instrumental ability (particularly guitarist Kim Simmonds) and clean, tight sound. An exciting LP-it’s difficult to sit still while it’s on, and that’s what the blues is all about, after all.” Rolling Stone observed, “Savoy Brown does not come on with complex technical artistry and does not attempt to overplay its music. Its strength lies in its group rapport and dynamics. Vocalist Chris Youlden is one of the better blues singers to emerge from England. His voice has the resonance and inflection so necessary to establish the power and emotion which is the blues.”

In June 1968, the group had released the single “Walking By Myself” backed with “Vicksburg Blues.” “Walking By Myself” was a strong ensemble piece showcasing Bob Hall on piano, the confident soloing of Simmonds, and a vocal duet between Youlden and Peverett. The group had by now refined its name to just “Savoy Brown” for this and subsequent releases.

From October 7 through 9, 1968 the band recorded the seminal “Train to Nowhere,” which one critic described as “droningly hypnotic in feel.” Youlden turned in powerful vocals on the record, and the band utilized a brass section for the first time (reportedly this included five trombones). It was later released as a single, with Rolling Stone citing “Train to Nowhere” as “certainly one of 1969’s real undiscovered single gems.” The recording also exposed the refined production skills of producer Vernon, who managed to build tension throughout the song, which in essence was a primitive one-line melody or modern “field-holler.” At the time, two days was an abnormally long period of time to spend in a studio recording and mixing just one track, but the results did, and still do, deserve far more critical and commercial acclaim. The flipside, the haunting “Tolling Bells,” was even more dynamic and, once again, the group succeeded in creating an insistent tension.

By late 1968, Savoy Brown’s schedule was booked solid with never fewer than six gigs a week. Audiences’ reactions was always enthusiastic, as Kim explained to Beat Instrumental: “Since we’ve got the new line-up together, the band has been working much better. Interest in our sort of music is on the upsurge, and we’re doing very well now.”

In November, the band discharged bassist Jobe and asked former member Brunning (who had recently filled in for some gigs) to join again permanently. Brunning again declined, and so Tone Stevens (b. September 12, 1949) joined instead.

On December 6, 1968, the band performed at the City of Leicester College of Education. The performance was taped with Dave Peverett substituting for Chris Youlden, who was sick and couldn’t sing well enough to perform. They recorded the set anyway, and three tracks, “Maybe Wrong,” “It Hurts Me Too” and “Louisiana Blues” appeared on their next album. “Louisiana Blues”, a largely instrumental song, became a showstopper on their forthcoming U.S. tour. A fourth live track, “Sweet Home Chicago,” appears to have been lost in the Decca vaults. All of Peverett’s vocals were re-recorded in the studio.

In December, the band returned to the studio to record more two tunes, “She’s Got a Ring in His Nose and a Ring on Her Hand” and “Don’t Turn Me from Your Door.” On January 22, 1969, they recorded “Grits Ain’t Groceries (All Around the World).” “Grits” was composed by Titus Turner and under the name “All Around the World” was a Top Ten r&b hit in 1955 as covered by Little Willie John. Little Milton revived the song in 1969 as “Grits Ain’t Groceries”. The song featured an explosive horn section and was paired with “Ring” for the U.S. market. In spite of the high calibre of both sides of this release, the single nevertheless failed to chart.

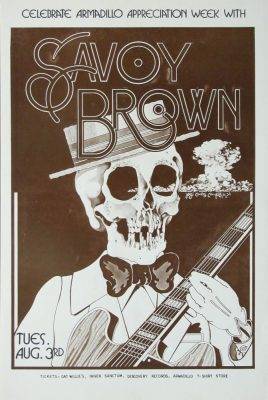

Savoy Brown began their first 10-week U.S. tour on January 24. They played both the Fillmore East and Fillmore West, and gigs in Chicago and Detroit along the way. At their first U.S. gig-a small New York club called the Scene (run by music veteran Steve Paul)-the audience reacted coolly. So there and then, Savoy Brown decided to liven up their stage act by giving Youlden more focus: he began taking the stage wearing a top hat and with a big cigar stuffed in his mouth. Velvet trousers and a black fur jacket completed the image. The band also added a long boogie to their set that, like “Louisiana Blues,” turned out to be a crowd pleaser. Kim later recalled the tour to Disc and Music Echo, “Until we hit Detroit-about half-way through the first tour-things weren’t all that great. Then suddenly we got a reaction that . . . well, even going back to Detroit now it couldn’t be repeated.” The tour proved to be a big success. Harry explained, “The good it’s done them is enormous. They are inspired by the great audience reactions. Whereas in England they used to wear dirty old jeans and just play the music, they really put on a show now. Kim doesn’t hide in the background on stage any more-he and Chris are right out in front.”

In May 1969, the band released their next album, Blue Matter. Consisting of previously released singles, live tracks recorded at Leicester with Peverett on vocals, and a John Lee Hooker cover, Blue Matter was a significant improvement over its predecessor. Melody Maker called it a “nice, meaty album and certainly the best we have had so far from this group” and Record Mirror said, “It represents a long jump from the twelve bar tribe and an immersion into what can be accomplished by stretching obsolete limits.” In spite of praise from the music press, the LP stalled at #182 on the U.S. charts and didn’t even make the charts in the U.K.

Later that month, the band held studio sessions for their next album (the last to be produced by Mike Vernon), A Step Further. Originally called Asylum, the album was released in the U.S. to coincide with the band’s second American tour, which was slated for four months commencing on June 17. One track, “I’m Tired,” was released as a U.S. single and reached #74 on the charts. Rolling Stone emphasized Youlden’s “marvellous vocal” and the song’s “irresistible rhythm.” The album continued the formula of the previous LP-one live side and one studio side. The best offerings were studio tracks: “I’m Tired,” the moody “Life’s One Act Play” and the upbeat Youlden composition “Made Up My Mind.” The live side was an endless boogie that Melody Maker called “quite remarkably boring, consisting of one riff recorded ‘live’ at Cooks Ferry Inn,” although it remains a favourite of Savoy Brown devotees. Kim himself was pleased with the result, telling Beat Instrumental, “I think the latest album, A Step Further, surprised a lot of people in that it was much heavier than anything we’ve done before.” Though not as strong as Blue Matter, the album nevertheless peaked at #71 in the U.S.

During the studio sessions for A Step Further, Hall, Peverett, Stevens and Earle started jamming on some old rockabilly tunes. Unknown to them, the engineer recorded these informal and spontaneous jams. After hearing the results, the foursome decided to create a rockabilly album and recorded a few more songs in the same vein, including the classic rock’n’roll standards “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” “Matchbox” and “Keep a Knockin’.” These recordings surfaced on 1969’s Rocked Out, issued as part of “The World of” series credited to “Warren Phillips and the Rockets.”

Savoy Brown’s second U.S. tour consolidated their initial success. Crowds in Detroit were especially enthralled, and Savoy Brown became the biggest act there since Cream.

Upon their arrival home, the band went on a U.K. tour with Jethro Tull and Terry Reid from September 25 to October 29, 1969. Harry again fired his brother Kim in December 1969, and the band actually played in BBC sessions without him. (Kim rejoined shortly thereafter).

In late January 1970, Savoy Brown embarked on their third U.S. tour, after which they returned to England to record the tracks for their next album, Raw Sienna (produced jointly by Kim and Youlden). The album was more complex than its predecessors, and Kim expressed satisfaction with the final product. “Raw Sienna is a personal achievement for me,” Kim told Melody Maker. “Both from the production side and musically. It’s our best album to date partly because everyone had so much freedom while we were actually recording.” Youlden’s compositions once again provided the highlights; the album incorporated more brass and jazzier arrangements such as “Hard Way to Do,” “Needle and Spoon” and “I’m Crying.” New Musical Express thought highly of the LP, printing, “A rich deep blues sound, especially from the bass (Tone Stevens) . . . with Chris Youlden producing the right sound on the vocals . . . and Kim Simmonds a powerful lead guitar.” Despite the press attention, Raw Sienna never caught fire, reaching only #121 on the U.S. charts.

[amazon_link asins=’B071JV92FC,B000065V8M,B000001FX0,B000001FX1,B000W1TJ9K,B000001FX3,B00BFBWY66,B000001FWZ,B000GIW8VU’ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’maasc-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’7c07213c-8c00-11e7-a13e-a74e430b2203′]

Discover more from Making A Scene!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.