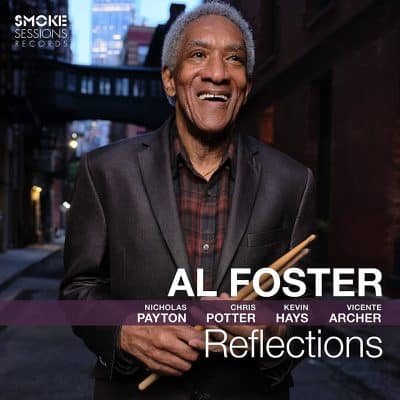

Al Foster Reflections

Al Foster

Reflections

Smoke Sessions

The recently turned octogenarian drummer Al Foster does not have many who can claim to have played with as many icons as he has. Only Ron Carter, Roy Haynes, and Jack DeJohnette come to mind. There are likely others but consider that at various points in his career, Foster was the drummer for Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Bobby Hutcherson, John Scofield, Pat Metheny, Charlie Haden, Randy and Michael Brecker, Bill Evans (the pianist), George Benson, Kenny Drew, Carmen McRae, Stan Getz, Toots Thielemans, Dexter Gordon and Chick Corea. Okay, take a breath. Whew! And as an upfront qualifier, this review may be a bit of a history lesson for the casual jazz listener.

An in-demand sideman of this stature doesn’t have many opportunities as a leader and Reflections is only Foster’s fifth, and second for the Smoke Sessions label. The lineup just has to be first caliber, right? Indeed, this hand-picked quintet features trumpeter Nicholas Payton, tenorist Chris Potter, pianist/keyboardist Kevin Hays, and bassist Vicente Archer, all of whom who have history with Foster.

So, what is it about Foster that attracted him to so many giants? Here’s a first impression from Miles Davis) with whom Foster played for 13 years in Davis’ fusion bands) – “He knocked me out because he had such a groove and he would just lay it right in there. That was the kind of thin I was looking for. Al could set it up for everybody else to play off and just keep the groove going forever.” This listener notices that Foster is unobtrusive and that he favors the lower end of the drums, the toms and bass drum without overplaying snares, cymbals and the flashier elements of the kit. Musicians admire his keen sensitivity, being able to listen to and play off other telepathically, always understated in his approach. For years Foster claims to have searched for his own identifiable style, being jealous of folks like Tony Williams, Joe Chambers, DeJohnette, and Max Roach but the history he proves that he indeed found it, saying he still comes up with tricks and creative ideas in his eight decade.

Here we have over an hour of music as Foster and crew deliver vital treatments of Davis, Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, and McCoy Tyner. Potter, Hays, and Payton each contributed, while Foster penned three, the two for Monk and another for his eldest granddaughter. Foster calls this one his best as a leader and it would be hard to miss with these musicians and these compositions. Foster claims that “most of my tunes have some Monk in them,” pointing not necessarily to the notes but the accents and that playful, unpredictable style of the piano great. “T.S. Monk” begins, a mid-tempo in the angular vein of Monk compositions, one that the soloists Payton, Potter, and Hays deftly navigate with their own convicted statements. The session ends with “Monk’s Bossa,” with Hays taking a bouncy excursion, Payton conjuring velveting tones from his horn, and Potter going into his ferocious beast mode. As we give you the background behind each of these tunes, we are indebted to the great jazz journalist and historian Ted Panken for the liner notes.

Rollins first tapped Foster in 1969 following the drummer’s gig with Monk and promptly fired him two days later. Rollins resumed the partnership nine years later and Foster eventually played on hundreds of Rollins’ gigs, recalling fondly a gig in Boston when Freddie Hubbard was in the band when they rendered the Rollins classic “Pent-Up House” from 1956 with Clifford Brown and Max Roach which this band revisits here, Foster noting that not many front-liners today except Payton and Potter could fire it with the same level of energy. Note that Foster hasn’t lost any of his bebop chops as his “bombs” propel those two and Hays in their fiery solos.

The album title implies nostalgia and indeed Foster recalls many favorite moments in forming this repertoire. Having played with McCoy Tyner for over two decades, Tyner was a natural choice, but Foster elected to perform a tune that preceded his tenure with the pianist, choosing “Blues on the Corner” from Tyner’s 1967 Blue Note classic, The Real McCoy with Joe Henderson, Ron Carter, and Elvin Jones. In this feature for Potter, Foster purposely avoids emulating Jones but chose the tune for its bluesy nature. Speaking of Henderson, whose “Punjab” he takes on here, from In n’ Out that also had Elvin Jones (with trumpeter Kenny Dorham, Tyner, and bassist Richard Davis). In the 1980s, Foster was the drummer on Henderson’s influential album The State of the Tenor, Vols.1 & 2 with Ron Carter and the association continued during the 1990s on long trio tours with other renowned bassists Charlie Haden and Dave Holland and on classic albums like So Near, So Far and The Joe Henderson Big Band. Herbie Hancock’s sublime ballad “Alone and I” nods to Foster’s many years recording and touring with the great pianist. It’s from Hancock’s Blue Note 1962 Takin’ Off with Dexter Gordon and Freddie Hubbard and understandably, proves to be a showcase for Hays.

That leaves Miles for the cover tunes and instead of reverting to familiar jazz-fusion territory, Foster does as with the others, he picks a preceding period, in this case bebop from 1947 with “Half Nelson.” It’s a contrafact of Tadd Dameron’s “Ladybird” that David presented with Charlie Parker on tenor no less. Payton emulates Fats Navarro in his tone while Potter leans more toward Dexter Gordon, who recorded this in 1978 with Louis Hayes, two weeks before Foster played on Gordon’s Biting the Apple. Hays, in turn, emulating pianist John Lewis who played on the original date. Foster, a vital cog in later period Miles, says this in the liners “I never really played jazz with Miles…Miles had his demons, but I loved him more than my father.” The closest we get to the fusion element is Payton’s tune “Six,” where Hays goes electric, Payton employs effects, and the band moves into the funky, intriguing style of Bitches Brew and On the Corner.

On the opposite tact, is Foster’s own lovely ballad, “Anastasia,” revealing that this unit can play with restraint as heard on Payton’s lyrical trumpet, Hays delicate touch, and Archer’s robust plucking. Similarly, Hays offers balladry with “Beat,” based on Sam Rivers’ “Beatrice,” featuring gorgeous, expressive turns from both Payton, Potter, and the pianist. Potter also elects the ballad route in his “Open Plans,” playing mostly in his searching, probing style along with Payton and Hays.

There’s nary a drum solo in the entire 68 minutes with Foster instead confidently steering these masters through this excellent session. The program spans three quarters of a century – appropriate for Foster, who remarkably just turned 80. Listen and then listen again focusing on his drumming. He never dominates but his presence is invaluable.

Al Foster

Reflections

Smoke Sessions

The recently turned octogenarian drummer Al Foster does not have many who can claim to have played with as many icons as he has. Only Ron Carter, Roy Haynes, and Jack DeJohnette come to mind. There are likely others but consider that at various points in his career, Foster was the drummer for Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Bobby Hutcherson, John Scofield, Pat Metheny, Charlie Haden, Randy and Michael Brecker, Bill Evans (the pianist), George Benson, Kenny Drew, Carmen McRae, Stan Getz, Toots Thielemans, Dexter Gordon and Chick Corea. Okay, take a breath. Whew! And as an upfront qualifier, this review may be a bit of a history lesson for the casual jazz listener.

An in-demand sideman of this stature doesn’t have many opportunities as a leader and Reflections is only Foster’s fifth, and second for the Smoke Sessions label. The lineup just has to be first caliber, right? Indeed, this hand-picked quintet features trumpeter Nicholas Payton, tenorist Chris Potter, pianist/keyboardist Kevin Hays, and bassist Vicente Archer, all of whom who have history with Foster.

So, what is it about Foster that attracted him to so many giants? Here’s a first impression from Miles Davis) with whom Foster played for 13 years in Davis’ fusion bands) – “He knocked me out because he had such a groove and he would just lay it right in there. That was the kind of thin I was looking for. Al could set it up for everybody else to play off and just keep the groove going forever.” This listener notices that Foster is unobtrusive and that he favors the lower end of the drums, the toms and bass drum without overplaying snares, cymbals and the flashier elements of the kit. Musicians admire his keen sensitivity, being able to listen to and play off other telepathically, always understated in his approach. For years Foster claims to have searched for his own identifiable style, being jealous of folks like Tony Williams, Joe Chambers, DeJohnette, and Max Roach but the history he proves that he indeed found it, saying he still comes up with tricks and creative ideas in his eight decade.

Here we have over an hour of music as Foster and crew deliver vital treatments of Davis, Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, and McCoy Tyner. Potter, Hays, and Payton each contributed, while Foster penned three, the two for Monk and another for his eldest granddaughter. Foster calls this one his best as a leader and it would be hard to miss with these musicians and these compositions. Foster claims that “most of my tunes have some Monk in them,” pointing not necessarily to the notes but the accents and that playful, unpredictable style of the piano great. “T.S. Monk” begins, a mid-tempo in the angular vein of Monk compositions, one that the soloists Payton, Potter, and Hays deftly navigate with their own convicted statements. The session ends with “Monk’s Bossa,” with Hays taking a bouncy excursion, Payton conjuring velveting tones from his horn, and Potter going into his ferocious beast mode. As we give you the background behind each of these tunes, we are indebted to the great jazz journalist and historian Ted Panken for the liner notes.

Rollins first tapped Foster in 1969 following the drummer’s gig with Monk and promptly fired him two days later. Rollins resumed the partnership nine years later and Foster eventually played on hundreds of Rollins’ gigs, recalling fondly a gig in Boston when Freddie Hubbard was in the band when they rendered the Rollins classic “Pent-Up House” from 1956 with Clifford Brown and Max Roach which this band revisits here, Foster noting that not many front-liners today except Payton and Potter could fire it with the same level of energy. Note that Foster hasn’t lost any of his bebop chops as his “bombs” propel those two and Hays in their fiery solos.

The album title implies nostalgia and indeed Foster recalls many favorite moments in forming this repertoire. Having played with McCoy Tyner for over two decades, Tyner was a natural choice, but Foster elected to perform a tune that preceded his tenure with the pianist, choosing “Blues on the Corner” from Tyner’s 1967 Blue Note classic, The Real McCoy with Joe Henderson, Ron Carter, and Elvin Jones. In this feature for Potter, Foster purposely avoids emulating Jones but chose the tune for its bluesy nature. Speaking of Henderson, whose “Punjab” he takes on here, from In n’ Out that also had Elvin Jones (with trumpeter Kenny Dorham, Tyner, and bassist Richard Davis). In the 1980s, Foster was the drummer on Henderson’s influential album The State of the Tenor, Vols.1 & 2 with Ron Carter and the association continued during the 1990s on long trio tours with other renowned bassists Charlie Haden and Dave Holland and on classic albums like So Near, So Far and The Joe Henderson Big Band. Herbie Hancock’s sublime ballad “Alone and I” nods to Foster’s many years recording and touring with the great pianist. It’s from Hancock’s Blue Note 1962 Takin’ Off with Dexter Gordon and Freddie Hubbard and understandably, proves to be a showcase for Hays.

That leaves Miles for the cover tunes and instead of reverting to familiar jazz-fusion territory, Foster does as with the others, he picks a preceding period, in this case bebop from 1947 with “Half Nelson.” It’s a contrafact of Tadd Dameron’s “Ladybird” that David presented with Charlie Parker on tenor no less. Payton emulates Fats Navarro in his tone while Potter leans more toward Dexter Gordon, who recorded this in 1978 with Louis Hayes, two weeks before Foster played on Gordon’s Biting the Apple. Hays, in turn, emulating pianist John Lewis who played on the original date. Foster, a vital cog in later period Miles, says this in the liners “I never really played jazz with Miles…Miles had his demons, but I loved him more than my father.” The closest we get to the fusion element is Payton’s tune “Six,” where Hays goes electric, Payton employs effects, and the band moves into the funky, intriguing style of Bitches Brew and On the Corner.

On the opposite tact, is Foster’s own lovely ballad, “Anastasia,” revealing that this unit can play with restraint as heard on Payton’s lyrical trumpet, Hays delicate touch, and Archer’s robust plucking. Similarly, Hays offers balladry with “Beat,” based on Sam Rivers’ “Beatrice,” featuring gorgeous, expressive turns from both Payton, Potter, and the pianist. Potter also elects the ballad route in his “Open Plans,” playing mostly in his searching, probing style along with Payton and Hays.

There’s nary a drum solo in the entire 68 minutes with Foster instead confidently steering these masters through this excellent session. The program spans three quarters of a century – appropriate for Foster, who remarkably just turned 80. Listen and then listen again focusing on his drumming. He never dominates but his presence is invaluable.

- Jim Hynes

Discover more from Making A Scene!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.