A Soundman’s Guide to Communicating With Musicians

A Soundman’s Guide to Communicating With Musicians

DON’T PANIC!

While the work can be very stressful at times, try to keep a cool head even when things aren’t going as planned. If you get stressed out the people around you will pick up on it. Then before you know it everybody is stressed out. By not getting stressed and causing others to worry you will find it much easier to solve problems as they come up.

Learn People’s Names.

This might seem like a minor thing, even trivial. It is not. Learning everybody’s name is one of the most important things you can do. It immediately creates a welcoming environment, builds trust, and makes all of your interactions feel more comfortable. I cannot stress the importance of this enough. Nobody likes being called “Hey bass player” or “Hey sound woman”. Always address people by name. It’s a better experience for everybody involved.

Everybody Has The Same Goal.

The performer’s job is to put on a show for the audience. The sound technician’s job is to make sure the audience can hear the performer. It’s all about the show. If a performer seems fussy about the sound, don’t take it personally; they’re just trying to make the show go as well as they can.

Don’t Be A Jerk.

Just don’t. Be respectful, get along, and resolve any problems by working together. Leave your ego at the door. You have a job to do, and that job requires you to work with other people. It doesn’t matter who you are or what your role is. Just be cool, okay?

For Technicians:

Get Ahead Of The Game.

Get your hands on the performer’s tech rider and stage plot in advance of the gig. Find out ahead of time what gear you will need and what gear is available at the venue. Make arrangements with your client to acquire any rental equipment that is needed. Make sure you are up front about the cost and the reasons why you need (or want) to rent equipment.

Not All Musicians Know Tech Speak.

As sound engineers, we’ve come to know and love our technical vocabulary, but not all musicians are fluent in this language. Artists don’t always know the technical end of things. Especially at the beginning of their music careers, though even some seasoned performers have trouble with the tech words. Sometimes when a sound tech might say “3 DIs, and 4 fifty-eights, and a fifty-seven” a musician might say “3 of those thingies to plug guitars into, four mics for singing, and the guitar on this side doesn’t have a plugin, so whatever doohickey you use when guitar doesn’t plug in”. You may want to correct them, this is a judgement call. Some people are more open to being corrected than others. Don’t ever belittle someone for their lack of technical knowledge. Your job is to take care of the technical things; their job is to play music. It is no more reasonable to expect a musician to know the difference between an active DI and a passive DI than it is to expect a sound tech to know an Fm9 from an Asus4 chord.

Be Hospitable.

A comfortable performer is a good performer. This goes beyond a good monitor mix, although that is important. Chances are that you are the primary point of contact for the performers when they arrive at your venue, so do whatever you can to ensure that the performers you are working with feel comfortable. Keep bottled water handy, offer it to the performers. Know where the bathrooms are. Know where they can find food near the venue. If possible, have some delivery menus handy as there is not always time to leave the venue for food after soundcheck.

Monitors Are Mixed For The Performers.

It doesn’t matter in the slightest what you think somebody’s monitor mix should sound like. All that matters is that each performer is hearing what THEY want to hear from their monitor. Some players want to hear pretty much the whole band, while other players basically just want to hear themselves. The only way to know for sure is to ask them. The key phrase for any monitor engineer is, “What would you like to hear?”.

This ties in with keeping the talent comfortable. A good monitor mix is one of the most important factors for a performer being comfortable on stage. Remember, the front of house mix is all about how you want to hear things, but the monitors are not. Come onto the stage and listen to the monitors at least once during soundcheck. If you can control the console remotely with a tablet, this is the best way to dial in monitors. You can stand next to each performer and hear their mix as you dial it in. At any rate make sure you know what the monitors actually sound like on stage.

Keep An Eye On The Stage During The Show.

Sometimes the monitor levels that you set at soundcheck need to be tweaked during the show. Watch for the signals: If you see somebody point to their mic and point to the ceiling it means they want more of their mic in their monitors. If you see a singer covering one ear with their finger, this is probably because they can’t hear themselves well enough. Turn them up if you see that. Always be gentle with mid-show adjustments, the last thing you want is a drastic change that results in feedback ringing out in the middle of a song.

For Musicians:

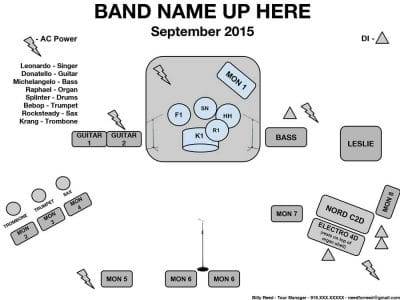

Send Your Stage Plot Well In Advance.

The sooner you send in your paperwork, the sooner the technical crew can start making sure they have everything you need for your show. I will cover drawing up a stage plot in-depth in a future article, but essentially a stage plot is just a drawing of the band on stage to indicate to the technicians where they will need to place each microphone, DI box, etc.

Understand your own setup.

Especially if your setup is weird. If a sound tech sees you have a mic and a multi-effect pedal in front of you, they will generally assume an instrument channel with effects and a vocal channel. If you’re running both your instrument and your voice through the pedal, the sound tech will need to know this so you need to be able to explain it.

If you play an instrument not commonly found in the region you’re performing, know how to mic it. If you play an Erhu (Chinese violin) for example, many sound techs you encounter in North America might not be familiar with your instrument. You will probably have to direct them as to where the microphone should go, what type of mic tends to work best, and possibly even what the instrument is supposed to sound like.

Understand Your Band’s Setup, At Least Generally.

Ideally you have sent your stage plot to the venue well in advance of your gig, but sometimes the paperwork gets lost. Maybe you’ve had a personnel change in the band since you sent in the paperwork. If you’re the first one to arrive at a venue you may be asked to give the technicians a quick rundown of the band’s setup. If you don’t know all of the technical details that’s okay. Few things will throw a sound tech off their game like getting conflicting information from different people, so if you don’t know the technical details just say so. However even just a basic picture of who plays what and where they normally set up on stage can be helpful. This is the minimum information you should be able to provide.

Know What You Want To Hear On Stage.

Don’t expect the sound tech to have any idea what you want to hear in your monitors. Generally, if you want to hear anything in your monitors you will have to ask for it. Maybe you only need your own voice and instrument in your monitor or maybe you need the whole band as well. It’s on you to request this because, as a rule, technicians subscribe to the philosophy that the less sound they have to send back to the stage, the better.

Know how to ask for monitor adjustments during a show.

A few times, I’ve had musicians come up to me after a show and say that they couldn’t hear themselves. After the show is not the best time to mention this, as I cannot help them after the show is over.

Understand that the from the front of house position, or even at a dedicated monitor console, technicians can’t really hear what’s coming out of your monitors. If you don’t tell them what you need to hear they won’t know. Also understand that there are often multiple monitor mixes on the deck and sometimes more than one of the same instrument. So “Can I get more guitar in the monitors,” is often not specific enough for a monitor tech to act on. “Can I get more stage-right guitar in the bass monitor,” should be enough for a sound tech to know which knob they need to turn.

If you find yourself needing a monitor adjustment mid-song, there are a few hand signals that are pretty well understood. Make eye-contact with your tech, point at what you want to hear and then up or down to indicate louder or quieter. It is never a bad idea to go over this with your techs at sound check to ensure you are on the same page about hand signals.

Conclusion.

Basically, it boils down to this: keep a cool head, don’t be a jerk, know what you need, know what others need from you, be respectful and be professional.

I’m going to close with an example:

A few years back I was running monitors at a local theatre for a show featuring a Burlesque troupe with dancers as well as a full band. At one point during the soundcheck/rehearsal one of the dancers approached me with a question about one of the tabs (curtains off stage that hide the wings), asking if it could be clamped back to make an on/off opening? I could have given a one word yes or no answer, but instead I paused, and thought for a second about why that curtain was actually there.

The reason for the drape being there in the first place was to hide any action in the wings from the audience. This was especially important in this instance as the dancers would be using the wings for costume changes! So I answered along the lines of “Well, if I’m standing here I can see a few seats in the house, and if you can see anybody in the audience, it means they can see you”. Apparently I answered correctly, as the dancer’s reply was “Oh, thank you so much! I’ll be sure to tell the other girls”.

She seemed pleasantly surprised. Maybe she had been expecting a stereotypical grumpy sound-tech answer like “the drapes aren’t sound gear so I don’t care”, or maybe she was not expecting the sound tech to be concerned with burlesque dancers’ privacy. I don’t know. What I do know is that after that moment, all of the dancers seemed to really like me, and the rest of the day went by very smoothly. I don’t think this had much to do with the curtain itself but had everything to do with the communication and respect I gave the performers.

SHARE THIS POST

Neal Miskin is a producer, engineer, singer/songwriter, and live sound engineer based in Vancouver BC. You can check out Neal’s music at https://nealmiskinmusic.bandcamp.com

Discover more from Making A Scene!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.