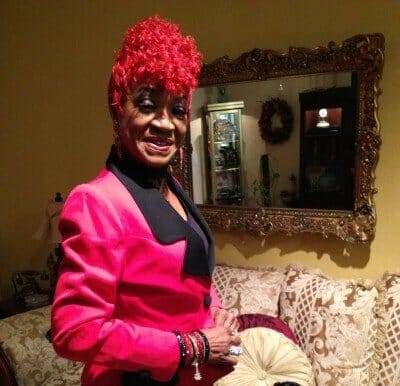

An Exclusive Interview with Trudy Lynn

AN Exclusive interview with Trudy Lynn by Richard Lhommedieu on Mixcloud

Trudy Lynn: International Blues Vocalist

Blues singer Trudy Lynn remembers her parents’ collection of 78 rpm records being both fragile and durable. She recalls their brittle quality: “You got a whupping back in those days if you’d break one of them,” she says. “They were like glass.” Yet the songs that spilled forth from those recordings have remained with her for decades.

Several years ago a friend gave Lynn a collection of songs by women blues singers from the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. “That’s where I’ve been the past few years,” Lynn says. “I started listening to what they were singing, and it’s like they knew my life before I even came here.

“Like my mother says, ‘There’s nothing new. It’s just new to you.’ That’s where this baby started.”

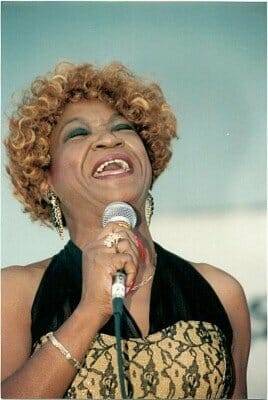

This baby is “Royal Oaks Blues Cafe,” the defining recording of Lynn’s career thus far. The Houston native has been performing for more than 50 years, but never before has the dynamic range of her voice been so sympathetically captured and brilliantly projected on record. She purrs, growls, whispers and blares the blues, with exquisite backing, particularly by collaborators Steve Krase on harmonica and John Del Toro Richardson on guitar. Producer Rock Romano expertly bottled their interactions.

Krase, who has shared stages with Lynn for more than 20 years, says he “had no idea she had that range. Some songs she’ll start with a growl and all of the sudden bring it up and hit a high note. I’m sure she’s done that before, but I hadn’t noticed it. I hear some different nuance in her voice on every single song.”

Lynn’s goal for the album was simple: to reinvent those timeless songs and, in doing so, restore the legacy of some performers who had been forgotten during the years as the blues steered toward a format dominated by men with guitars. Lynn and Krase’s song selection was smart and sympathetic to her voice, which updates songs originally made by artists like Clara Smith, Eloise Bennett, Bea Booze and Viviane Greene.

“Women used to rule back in the day,” she says. “A lot of great artists – even guys like Louis Armstrong – they played in these ladies’ bands when they were young, blues bands and minstrel shows. It’s a lot like now, days where you have a lot of great singers who don’t get enough recognition. So many great singers.”

Lynn sometimes treats conversation like a refrain in a song. She strings together a series of thoughts and emphasizes them with a succinct summarizing sentence, which she then repeats a few times, her voice growing quieter with each repetition. She calls this “echoing myself.”

She has put her voice to a lot of different music during the years, having sung soul, R&B and country music. But, she says, “There’s just one of them that you master. I chose the blues. I love the blues. I love the blues. Love the blues.”

Lynn, 66, was born Lee Audrey Nelms in the Fifth Ward. In addition to her parents’ 78s, she had a lot of casual contact with blues and R&B performers because her mother ran a beauty shop by the Club Matinee. Lynn would walk there from school trying to catch a glimpse of acts like Joe Hinton or Bobby “Blue” Bland, who would play the venue. She wasn’t able to get closer to the music than the club’s door. “There wasn’t any going in there,” she says. “The way we were raised, everybody could whup your butt in the neighborhood. The neighborhood raised all the children where I grew up, not just your parents.”

Lynn’s parents didn’t push music on her, nor were they discouraging. She sang in a vocal ensemble at Wheatley High School. Her first break came as a teen when late blues great Albert Collins – playing with Big Tiny and the Thunderbirds – invited her onto the bandstand at Walter’s Lounge on Lockwood. She sang “Night Time Is the Right Time.”

“I was in, baby,” she says. “I said, ‘Oh yes, this is what I want to do. This is what I want to do.’ “

After high school, Lynn went to visit her aunt in Lufkin, where a club called the Cinderella needed a singer. She decided Lee Audrey Nelms wasn’t going to cut it as a stage name. The club had a bunch of cartoon character names painted on the wall and she noticed “Trudy,” which she quickly paired with Lynn. “Lynn was something in those days,” she says. “Gloria Lynne, Barbara Lynn. I thought, ‘I’m going to be one of those Lynns, too, baby.’ “

Her repertoire was limited: “Stormy Weather,” an Etta James song called “Tell Mama” and a third song she can’t recall. But Lynn set about expanding her song book.

She found some work singing in big bands that would play military bases around the state and also sang soul music for a time. The great guitarist I.J. Gosey took notice and recommended Lynn to Clarence Green, a blues guitarist and bandleader. Lynn spent five years as vocalist in his band.

Green was a stern mentor, but Lynn credits him with helping her become a professional. “He molded me well,” she says. “He’s still in me because of what he taught me. It takes that. It takes that. It takes that.”

After leaving Green’s band, Lynn began performing on her own. She made a fine single “What a Waste/Long Live the Blues” in the early ’70s, which helped her with some bookings, but Lynn recorded only sporadically. For years she struggled to get recorded in a manner deserving of her talent.

A British fan who moved to Atlanta started an independent label there in the 1980s and provided the best platform for Lynn to that point. Lynn’s time in Ichiban Records likely peaked in 1993 with “I’ll Run Your Hurt Away.”

But often, producers had a strong hand in directing her recordings. With “Royal Oaks Blues Cafe,” Lynn played curator for herself. She wrote two strong tracks – “Every Side of Lonesome” and “Down in Memphis” – that blend nicely with the vintage songs. The record opens vibrantly with “Confessin’ the Blues” and concludes on a bawdy note with “Whip It to a Jelly.”

Between are songs about good times and bad men. “Each one of these songs means something to me,” she says. “I truly understand something about each one of them.”

Lynn says the recording “is just the beginning,” as she plans to continue researching decades-old blues songs for future use.

But prior to returning to a recording studio, Lynn plans to take the record on the road. The market for blues isn’t what it was during the ’60s, but she says many viable places remain for a classic blues singer in the 21st century.

“People say this place or that place ain’t got no blues, well, so go to where the blues is,” she says. “Go to Europe, find the American festivals. You don’t do it because there are places to play. In order to do it, you’ve got to love it.

“Musicians want to work with me, they say, ‘I can play some blues.’ Yes, but are you a blues musician? There’s no jamming. You’ve got to play your part. Play it until it gets monotonous. You’ve got to feel it. You’ve got to feel it. I’m just echoing myself. I do it all the time.

“But you’ve got to feel it.”

Discover more from Making A Scene!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.